Marigolds (zempoalxochitl, flower of the dead) and purple mota for sale in the Patzcuaro market for Day of the Dead. Photo by Grace Relfe.

Dia de los Muertos,

Day of the Dead, celebrated in Mexico and other Hispanic countries, has considerable religious significance and predates the conquest of Mexico by Hernando Cortez.

Marigolds (zempoalxochitl, flower of the dead) and purple mota for sale in the Patzcuaro market for Day of the Dead. Photo by Grace Relfe.

The festive period begins on the night of October 31, and continues through All Saints Day and All Souls Day, celebrated November 1st and 2nd respectively. On the night of October 31st, in rituals that recall the ancestor worship of their Indian forefathers, many Mexican families erect altars to the dead in their homes, as well as in the cemeteries where their loved ones are buried. Included in these altars are ofrendas, offerings of the favorite foods and drinks of the departed, to be enjoyed by their spirits when they return to visit their loved ones. The altar is laden with bright orange marigolds (the zempoalxochitl, flower of the dead) and mota, a deep purple velvety flower, and is lighted with a multitude of candles. Traditionally, the altar is lighted on the evening of the 31st to await the arrival of the dead children, los angelitos. At twilight on November 1st until dawn of the 2nd, the altar is again lighted and this time the vigil is for the departed adults.

A Happy Time of Communion with Death

This is a time of happy communion with the dead, not a time of sorrow. Nobel Prize winner, Octavio Paz, in his essay, The Labyrinth of Solitude explores the Mexican fascination with the duality of life and death. “Our relations with death are intimate,” Paz writes, “more intimate perhaps than those of any other people.” He further described this almost ghoulish celebration as an escape from the difficulties of every day existence – not only the poverty, but also a kind of blackness in the soul which perhaps has its roots in the joining of two antagonistic groups, the Indian and the Spanish. Whatever the reason, this Mexican fiesta is a full-blooded affair, colorful, highly emotional and it lasts for days.

On Dia de Los Angelitos, (Day of the little Angels), the souls of the little children are said to return home. They find an abundance of candies, cookies, milk and honey and other favorite foods awaiting them. Nearby toys are placed for them to play with after they finish eating.

The following night, November 1st, is for the returning adult souls. They are greeted with more abundant fare; turkey with mole (chocolate and chile sauce), chayote (a squash-like vegetable), a favorite drink and pan de muertos, bread shaped in the forms of skulls and skeletons.

Additionally, tequila, pulque, or other local fermented drink is available in abundance.

These remembrances usually take place in the local cemetery and in the homes an altar is prepared and is visited by friends and neighbors of the newly deceased.

Friends and family usually celebrate both nights, often talking with the departed ones in a very convincing manner. They rarely partake of the food prepared for the spirits, but later give it to friends or less fortunate neighbors. In rural Mexico it is not uncommon for the local curandero (healer or wise man) to say a mass for the recent dead. This is followed by great amounts of tequila, tamales for the living, and a night of dancing, song and bonfires.

On the Island of Janitzio in Michoacán

The most colorful celebration in Mexico is probably on the Island of Janitzio, in the middle of Lake Patzcuaro high in the mountains between Guadalajara and Mexico.

As night falls the lights of thousands of candles are seen in the hands of the Purepecha Indians as they make their way to the cemetery. The women, wearing heavy black pleated skirts, embroidered aprons and blouses, their black braids adorned with yarn and ribbons carry offrendas (offerings) of elaborately formed bread, to the graveyard where they will sit by graves of their loved ones to await the souls who travel through the pines and over the lake to visit with them. Sounds of violins and guitars drift across the waters to the mainland with melodies of ancient times.

Early on the morning of November 1st, the Purepecha men climb into their dugout canoes and paddle out on the lake in search of wild duck. They circle around the ducks and hurl harpoon-like weapons, called atlatl, at the ducks. When this long bamboo spear, a prized weapon for the Indians since 2000 B.C. hits its mark it stands upright in the water. The ducks are prepared in spicy sauces on open fires throughout the village and feasted upon by all.

Death in the marketplace

For weeks before the celebration, death is marked in the stores and on the streets in Mexico in the form of tiny skulls of spun sugar, elaborately decorated sugar skeletons and many coffins of candy. Children are eager to have death’s head masks and amuse themselves with toy funeral processions and miniature altars made of wood or clay.

Death is also the theme of the Calaveras (literally skulls, or skeletons) which are mock obituaries or satirical versus appearing in local newspapers at this time of the year. The verses and writings often spoof politicians and film stars and may touch on matters that cannot be otherwise discussed.

Life Depends on Death

While the Spaniards arriving in the new world brought with them the Catholic All Saints’ and All Souls days, the Indians they found in the Americas already believed that life depended on death. The Mayans, who believed man sprung from the corn plant carved corn plants into the tombstones. The corn plant is the Mayan symbol of life and fertility. The Aztecs believed that the god Quetzalcoatl poured his blood over the bones of his ancestors gathered from Mictlan, (home of the dead), to begin the human race.

Glimpses of the festivities can be found in towns and cities throughout the United States where there is a Mexican population. In Mexico, the most colorful celebrations are found in the states of Michoacán and Oaxaca. However the visitor has only to visit the cemetery in any small village on November 1st, to find it adorned with bright gold flowers, candles and the remnants of a feast prepared for a departed soul.

- Marigolds (zempoalxochitl, flower of the dead) and purple mota for sale in the Patzcuaro market for Day of the Dead. Photo by Grace Relfe.

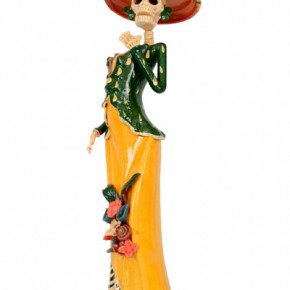

- La Calavera (literally skull, or skeleton) is a common symbol seen during Day of the Dead.

- Brightly colored candy commemorating Day of the Dead. Photo by Grace Relfe.

- Brightly colored candy commemorating Day of the Dead. Photo By Grace Relfe.

- Marigolds (zempoalxochitl, flower of the dead) and purple Mota for sale in the Patzcuaro market for Day of the Dead. Photo by Grace Relfe.

- Colorful alters and brightly colored candy commemorating Day of the Dead. Photo by Grace Relfe.